The 6th

LaureateTheatre/Film

John Gielgud

Sir John Gielgud was widely regarded, ex aequo with his friend and fellow knight, Laurence Olivier, as England’s greatest actor of the twentieth century. A remarkable feature of his talent was his readiness to renew himself, as both actor and director, by constantly extending his range. For virtually seven decades he regularly alternated between the traditional and contemporary repertoires. What made him unequalled in both was his mastery of fundamental paradox, playing weakness with strength, for instance, and sleaziness with elegance and aplomb. For him, the meaning and emotion of a dramatic text were communicated above all through gesture and voice – the voice that one critic likened to a Stradivarius, and which was one of the supreme glories of the modern British stage.

Biography

From his debut at London’s Old Vic theatre in 1921, at the age of 17, Sir John Gielgud was universally regarded, ex aequo with his close friend and fellow knight, Laurence Olivier, as England’s – as well as the English language’s – greatest actor, blessed as he was with a voice which was one of the supreme glories of the modern British stage and a capacity for externalising an internal passion without resorting to ranting, barnstorming histrionics.

The most extraordinary quality possessed by Gielgud was, perhaps, the ineffable serenity, even sweetness, of his theatrical disposition, with the result that his dramatic roles were rendered all the more memorable by the rigid control which his classical training, allied, yet again, to that uniquely mellifluous voice, maintained over them. There had never has been an actor of John Gielgud’s calibre and, it can safely be assumed, there never again will be.

Since Gielgud was born into a family with propitious stage connections – his mother Kate was related to the Terrys, one of the most prominent of theatrical dynasties in England – it would have been strange indeed had he not decided to become an actor. Yet so patent was his genius that he was never forced to work his way up through the ranks of his chosen profession. Only five years after his first teenaged appearance he was hired to replace Noël Coward, no less, in the leading role of Margaret Kennedy’s long-running slice of whimsy, The Constant Nymph. And thereafter, for virtually seven decades, with a versatility which may to some have seemed at odds with his slightly precious public image, he would regularly alternate between the traditional and the contemporary repertoire.

What made Gielgud unequalled in both of these repertoires was that he soon mastered one of the fundamental paradoxes of the actor’s condition: that of playing weakness with strength (for example his King Lear, a role he played more than once: ‘O Lear, Lear, Lear! Beat at this gate, that let thy folly in’), ineffectuality with power (as the perpetually embarrassed Gaev in Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, one of his favourite plays by one of his favourite dramatists), even seedy, down-at-heel sleaziness with true elegance and aplomb (as an obnoxious sponger in Harold Pinter’s No Man’s Land). Unlike Olivier, however, he was no lover of masks. He tended to look the same whatever he played and had no truck with wigs, false noses or elaborate make-up. For him, the meaning and emotion of a dramatic text were communicated above all through gesture and voice (the voice that one critic likened to a Stradivarius) – to the point where, as in his legendary Richard II on stage or his ethereally ailing Henry in Orson Welles’ film of Chimes at Midnight, one had the impression that his body had somehow become eerily translucent, a vitreous casing for his vocal chords.

Another remarkable feature of Gielgud’s talent was his audacity, his readiness to renew himself, as both actor and director, by constantly extending his range. Nothing could have satisfied him less than the complacent merry-go-round (or, maybe one should say, weary-go-round) of endless classic revivals, Shakespeare turn about with Chekhov, Chekhov turn about with Shaw, Shaw with Congreve, and so on ad nauseam. Seemingly blessed with the gift of eternal youthfulness of taste and spirit, he ventured into the dissimilar imaginative worlds of Somerset Maugham and Emlyn Williams, Terence Rattigan and Christopher Fry, Graham Greene and Peter Shaffer. Even in the post-sixties era, when the British theatre was recharging its batteries with the dark energy of working-class themes (and, concurrently, benefiting from a greater candour in the treatment of sexuality), Gielgud adapted his style to accommodate the demotically vernacular rhythms of such playwrights as Pinter, David Storey and Charles Wood.

Nor was he content to confine himself to the theatre alone. As early as 1936, Alfred Hitchcock cast him in the leading role of the spy Ashenden in his adaptation of a Maugham novella, Secret Agent. But romantic jeunes premiers were not really his forte, and it was not until the second half of his life and career that his gifts were properly exploited in the cinema. He made a brilliant Cassius in Joseph L Mankiewicz’s Julius Caesar (alongside Marlon Brando’s Mark Antony); offered a memorable portrait of a witty, bilious novelist vainly struggling to fuse memory and imagination into a coherent fiction in Alain Resnais’s Providence; and then gleefully sent himself up (and, to his own amazement, won an Academy Award) as an urbanely foul-mouthed ‘gentleman’s gentleman’ in Arthur.

The dramatist Christopher Fry once wisely said of Gielgud that he approached every performance ‘as though he were always at the beginning of his career’. It could not be better put. For all his experience, and for all the promises already gloriously kept, he always remained the most eternally promising of actors.

Gilbert Adair

He passed away on May 21, 2000, Aylesbury, England

Chronology

First film appearance as Daniel in Who Is the Man?

Host in The Pallisers (TV series)

Edward Ryder in Brideshead Revisited (TV series)

-

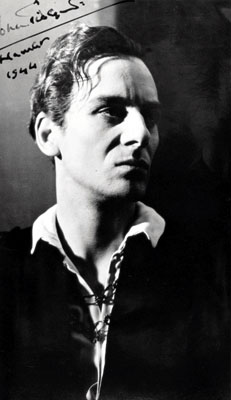

Hamlet

-

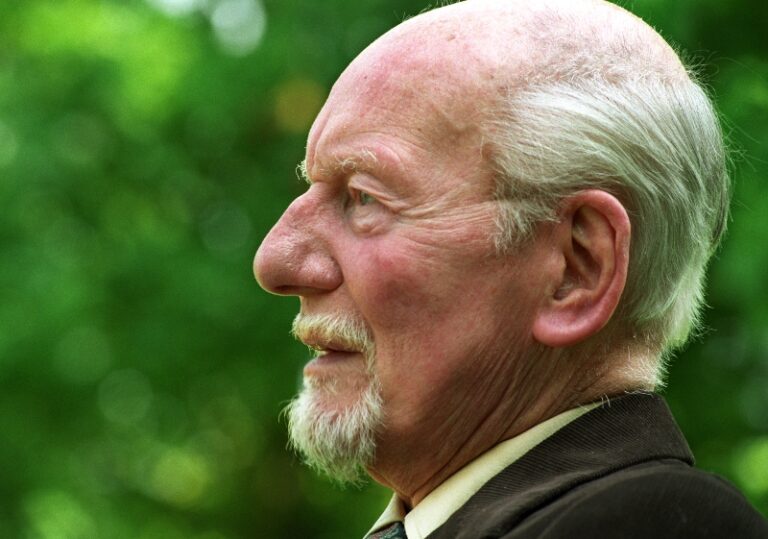

John Gielgud by David Hockney

-

Prospero's Books

-

At his home

-

At his home