The 11th

LaureatePainting

Anselm Kiefer

A complex critical engagement with history runs through all Anselm Kiefer’s work. His paintings and the sculptures of Georg Baselitz caused a storm at the Venice Biennale of 1980: viewers had to decide whether the inclusion of apparently Nazi imagery was ironic or intended to provoke new waves of fascist sentiment. Kiefer was working in the belief that art could offer salvation to a traumatised nation and to a confused, divided world. In massive canvases he created epic images, invoking the history of German culture through figures such as Wagner and Goethe, and continuing the tradition of history painting as a means of addressing the world. Few artists working today have such a deep sense of art’s engagement with the past and with the morality and ethics of the present, or express so profoundly the possibility of redemption through human endeavour.

Biography

Born in Germany as the second world war ended in Europe, Anselm Kiefer inherited a collapsed spiritual and physical world struggling to regain its self-respect. In cultural matters the priority was then to join in, to perform honourably on the international stage. That meant rehabilitating the heroes of German art, recently denounced as decadents, and showing that Germany still had creative individuals able to work alongside the leading figures in western art. Reconnect with modernism, and the sap may rise again from those old, not wholly severed, roots.

This was not to be Kiefer’s road. Influenced by Horst Antes, his teacher in Karlsruhe, and by Josef Beuys, his mentor in Düsseldorf, Kiefer decided that art’s duty was to bring salvation to a traumatised nation and to a confused, divided world. He embarked on this mission in 1969. In books of his photographs, with and without words, and soon also in watercolours and large paintings, he explored his country’s recent aberration, drawing on history and myths as well as landscape images significant to the Romantics. His idiom was graphic more than painterly; this too linked him to the dominant traditions of German art. He found some of his strongest imagery in The Ring of the Nibelung, Wagner’s compound of Nordic legends glorifying the lust for power, an abiding workof genius seized on by fascism. His studio in the Oden Forest, close to the Black Forest and pregnant with national significance, served as his stage for large paintings such as Nothung, 1973 (Rotterdam, Museum Boymans-can Beuningen), showing Siegfried’s sword set in that brusque timber hall.

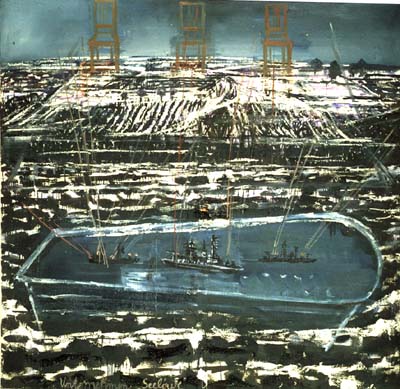

Kirchner was shouldering the whole of German history and culture, mostly through its heroes, from Hermann (Arminius), victorious over the Romans, to the great philosophers, mystics, generals, poets and composers, named selectively in Germany’s Spiritual Heroes, 1973, (New York, Barbara and Eugene Schwartz collection), and portrayed in woodcuts assembled around burning trees in Ways of Worldly Wisdom – Arminius’s Battle, 1978–80 (Chicago, Art Institute). It was not clear, at first, whether he was glorifying or warning against an inheritance that had climaxed so disastrously. When he exhibited such images in the German pavilion at the 1980 Venice Biennale, its main space occupied by Baselitz’s rough-hewn timber figure, fallen but still making the Nazi salute, their joint meaning was hotly disputed. Kiefer continued to create epic images, again in books and large paintings, of historic areas of Germany, famed for and desolated by war, such as the Brandenburg Heath of East Germany, and of actual and potential key moments, such as Hitler’s planned ‘Operation Sea Lion’ against England and Hermann’s victory over Varus, retold by poets to celebrate Germany’s liberation and by the Nazis to inflame xenophobia. What had seemed dangerously ambiguous soon, through his invoking ancient symbolism, and then adding a painter’s palette – at first ghostly, in lines of paint, then awesomely real, a lead sheet form attached to the canvas – was revealed as a programme of awareness building.

The palette is constructive, the sword destructive; both are powerful. They confront each other in iconoclasm, medieval and modern. He painted with sand, straw and other materials, as well as lead, together with oil, emulsion and acrylic; fragility accompanies his vehemence amid desolation. Influenced by the poems of Paul Celan, a voice from the concentration camps, Kiefer from 1981 on explored the dual metaphor of Margarete, Goethe’s blonde-haired Gretchen, represented by fragile straw, and Shulamite, the ashen-haired Jewess, in black paint. Nuremberg too provided a double image, as the fine historic city celebrated in Wagner’s The Mastersingers and also mocked for its traditionalism, but recently the home of Nazism’s most clamorous rallies. Watercolours of 1980–82, showing a palette surrounded by fascistic classical architecture, are dedicated ‘to the Unknown Painter’.

Kiefer’s pain and pessimism are unmistakable; we should also note his periodic turn to thoughts of redemption through human endeavour. The Jews’ exodus from Egypt and Moses’s parting of the Red Sea became source material for him in the mid-1980s, with Aron as an ambiguous artist-like figure and the zinc bathtub used to picture Operation Sea Lion doubling now as the Red Sea. Always fascinated by alchemical procedures, Kiefer began to submit his paintings to physical transmutation by burning and fusing. Out of blackness a new world may be born; the Iron Path, 1986, (Wynnewood, Penn., David Pincus collection) must be pursued. Books, too, belong to the past and the future. (A book of The Books of Anselm Kiefer has been available around the world since 1991.) In 1889 he completed The High Priestess, a mighty metal sculpture of shelves bearing gigantic, unopenable lead books, awaiting perhaps the hand of some superman. He continues to work dramatically in two and three dimensions, re-asserting the importance of ‘history painting’, traditionally honoured as visual art’s prime means of addressing the world.

Norbert Lynton

Chronology

-

Unternehmen "Seeloewe", 1981

-

Heroische Sinnbilder, 1975

-

Heroische Sinnbilder, 1975

-

Die Meistersinger, 1981

-

Melancholia, 1989

-

Cette obscure clarte qui tombe des etoiles, 1996

-

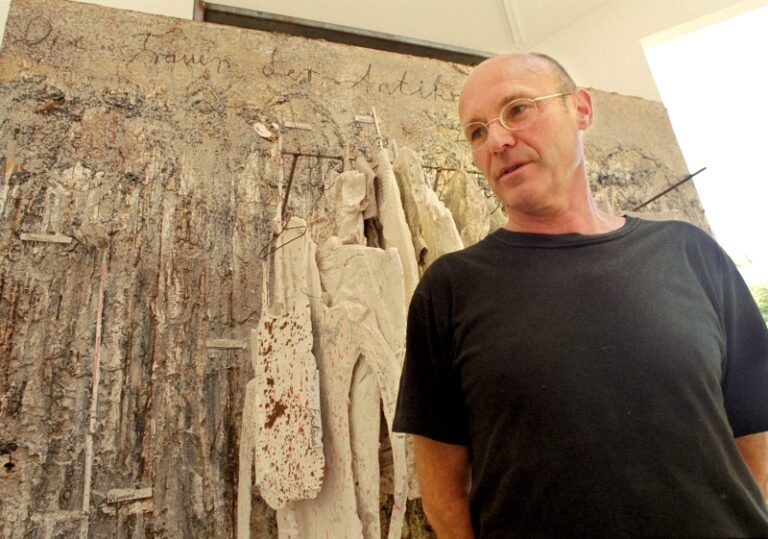

Kiefer in his studio, 1999

-

Kiefer in his studio, 1999