The 7th

LaureateArchitecture

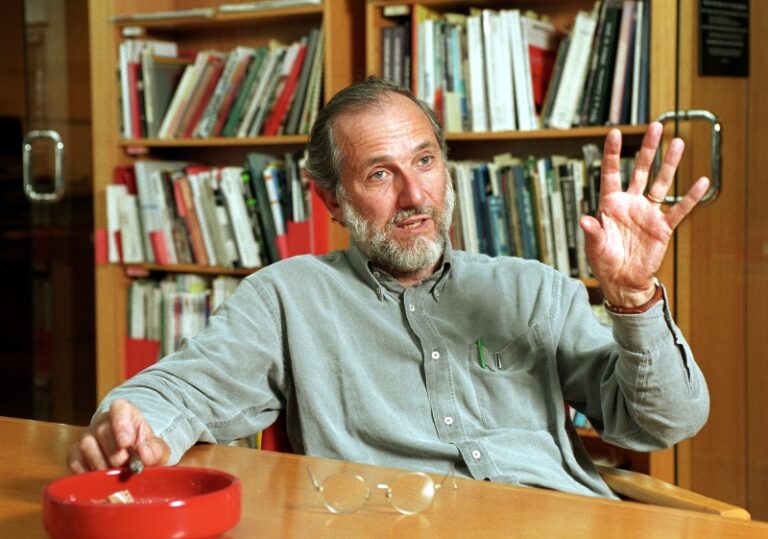

Renzo Piano

From his first major work, the Pompidou Centre in Paris, to his most recent, the masterplanning of the Potsdamer Platz redevelopment in Berlin, Renzo Piano’s architecture has been bounded on one side by the challenge of innovation and on the other by the limits of tradition. While always influenced by the possibilities opened up by new technologies in design and building, Piano recognises at the same time that the roots of architecture lie in history and nature. Thus a recent building such as the Cultural Centre in Noumea, New Caledonia refers formally to aboriginal huts, while the stunningly bold Kansai Airport in Osaka is a masterpiece of high-tech design and material construction. Through this mixture of formal and technical innovation, Piano remains a central figure in world architecture.

Biography

If any single architect practising today has challenged the accepted division of labour between architect and builder, that architect is Renzo Piano. Piano has always been determined to maintain and expand his direct control over the building process by designing dry assemblies which have to be erected according to a specific and predetermined procedure.

What distinguishes his work from that of other high-tech architects is the varied expressivity of his Produktform, for while the rigour of his design method has been maintained throughout his career, the character of the result has differed markedly from one project to the next. This is evident in two works that he realised in Genoa in 1966, at the very beginning of his career. In each building a totally different tectonic paradigm was adopted: in the first instance an undulating tensile roof made of steel and polyester covering an industrial shed; in the second, the orthogonal syncopation of a set of prefabricated concrete panels employed in the realisation of a block of flats. The Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, the competition for which he won in collaboration with Richard Rogers in 1971, revealed more clearly the various influences that would play salient roles in Piano’s development: first the British Archigram group, whose science fiction projections anticipated the image of the Centre Pompidou; then, in descending order, the work of the pioneering space-frame engineer Z S Makowski, the light-weight metal constructions of Jean Prouvé, and Richard Buckminster Fuller who, as Piano put it, ‘raised questions about the great themes of architecture in a very free and nonconformist way.’ From Pier Luigi Nervi he assimilated the structural advantages of folded slab construction, while certain Italian architect/designers clearly influenced his attitude towards detailing, perhaps most notably Marco Zanuso, whom he assisted at the Milan Polytechnic, and Franco Albini, with whom he served his apprenticeship after graduating from the school.

While all these influences played a decisive role in determining the ingenious form of his wood and plastic, demountable IBM Travelling Pavilion of 1982, Piano turned once again to confront the theme of the art gallery as a flexible space in his understated De Menil Museum in Houston, Texas, USA, completed in 1986. This work was designed in close collaboration with the British engineer Peter Rice, who served as Piano’s consulting engineer from the building of the Centre Georges Pompidou until Rice’s untimely death in 1991.

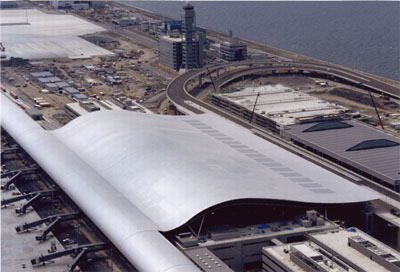

Perhaps the most exceptional aspect of the Renzo Piano Building Workshop (founded in 1981) is the remarkable scope and scale of its mature work, with buildings covering a wide typological spectrum involving a great variety of form, material and structure. This versatility becomes evident as one passes, in a decade, from the San Nicola Stadium in Bari, Italy, capable of accommodating 60, 000 people for the 1990 World Cup, to the Rue de Meaux housing in Paris of 1991; or, say, from the vast Kansai International Airport in Osaka of 1994 to the J M Tjibaou Cultural Centre in Nouméa, New Caledonia, completed in 1998.

Throughout the last decade the Workshop’s practice has spanned the globe from Northern Europe and the Mediterranean to Southern Japan and a remote island in the Pacific. Within this global scope, Piano’s repertoire in terms of structures, membranes and images has passed from the heavy, cantilevered, partly prefabricated form of the stadium, capped with a light teflon parasol, to the tessellated terra-cotta and cement façade of the Rue de Meaux, or from the elongated stainless-steel shell of the air terminal to the monumental mahogany ‘cases’ of Nouméa, which rise, basket-like, high in the air, so as to recall the aboriginal form of the Kanak hut. These ‘cases’ serve to house certain facilities in the cultural centre. In each instance the tectonic expression has been chosen to accord not only with the character of the institution, but also with the demands of climate, function and the mode of production.

The scale and scope of Piano’s practice shows little sign of diminishing, as he passes from the post-tensioned stone arches of his Padre Pio Church in San Giovanni Rotondo to the terra-cotta clad Daimler-Benz offices of his Potsdamer Platz reconstruction in Berlin. One cannot fail to remark on the salient role played by computer-aided design in the whole of Piano’s output, ranging from the roof trusses of the Kansai terminal, which vary constantly in section, to the precision cutting of the stone voussoirs for the church.

Yet despite this use of new technologies, Piano remains convinced that the architect must lead a double life, on the one hand pushing the discipline to its limits while on the other recognising that its roots are irreducibly grounded in history and nature; bound on one side by the challenge of innovation and on the other by the limits of tradition.

Kenneth Frampton

Chronology

-

Underground Station

-

San Nicola Stadium

-

Kansai International Airport

-

Kansai International Airport

-

Beyeler Foundation Museum, Basel

-

J M Tjibaou Cultural Centre, Noumea