The 2nd

LaureateArchitecture

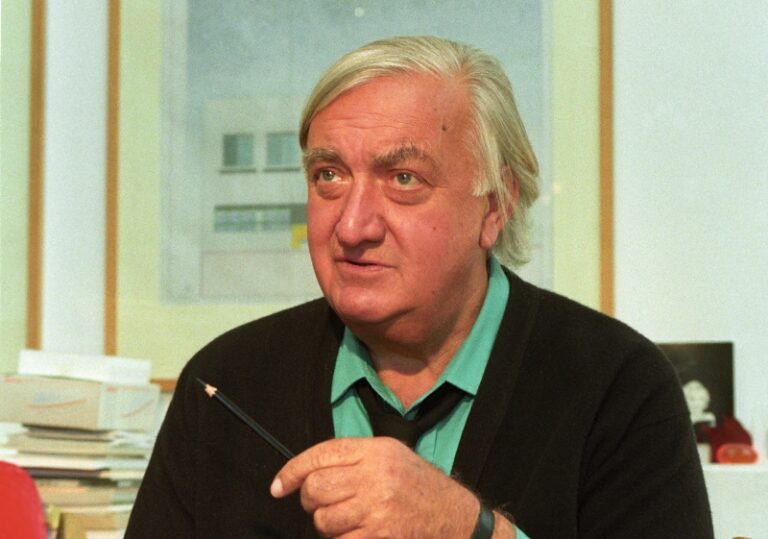

James Stirling

James Stirling’s early work,while being influenced by the new brutalist movement of the 1950s,showed an awareness of vernacular forms and a sense of material and constructional economy that would be fully revealed in his mature work for museums and city spaces. The university buildings in the UK of the 1960s established Stirling’s brutalist reputation,a tendency that began to be moderated by a discernible neo-classical spirit in the 1970s. The Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart announced his mature manner,an enlightened postmodernism in which ‘pop’ constructivism and neo-classical elements feed and fire off each other. This building and the succession of related works that followed have achieved a popularity that is rare among new buildings of any kind,let alone those of such profound architectural literacy.

Biography

James Stirling’s architecture may readily be associated with the new brutalist movement of the 1950s even if he was not,strictly speaking,an advocate of this position. All the same,it is evident that he and his initial partner,James Gowan,elected to interpret the British brick vernacular in such a way as to create a rigorously modern mode for building in an inclement northern climate.

Influenced by Le Corbusier’s postwar excursus into the vernacular (particularly his Maisons Jaoul of 1956),nothing could have been further from the mythical white architecture of the pre-war period than Stirling’s domestic architecture of the mid-fifties – from the infill village housing schemes that he and Gowan submitted to the CIAM X meeting in Aix-en-Provence in 1955 to the two-storey,load-bearing brick housing they realised at Ham Common,near London in the same year.

The syncopated,modulated rhythm of the Ham Common complex reappeared in somewhat more classical terms in their remarkable competition entry for Churchill College,Cambridge of 1958. By this date Stirling was subject to two rather contradictory influences: on the one hand the tradition of European constructivism; on the other,the work of Louis Kahn. Both of these influences are evident in the canonical Engineering Faculty building that he and Gowan realised for the University of Leicester in 1959. As arresting for the sculptural power of its overall form as for the organicism of its component parts and the efficiency of its organisation,the Leicester Engineering Faculty established Stirling and Gowan’s brutalist reputation and led directly to a series of university buildings in a similar idiom,capitalising on the combination of precision brickwork with patent glazing. This series includes the Cambridge University History Faculty building of 1964 and Stirling’s Queen’s College,Oxford of 1966. The end of this particular sequence,accompanied by a marked shift from precision brickwork to prefabricated concrete,came with the stepped residential blocks built for St Andrews University in 1964. This work effectively signalled a hiatus in Stirling’s development,precipitated by Gowan’s departure in 1963 and,in 1969,the arrival of Leon Krier as an influential assistant.

While Stirling had always been susceptible to the influence of Alvar Aalto’s organicism,a discernable neo-classical spirit began to enter his work at around this time. This first became evident in a 1969 competition entry for Siemens AG in Munich,then in other competition projects in Germany,for art museums in Düsseldorf and Cologne submitted in 1975 and 1976,and also in his 1977 design for the new Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart,a building which was finally opened to the public in 1984. In many ways the Staatsgalerie was the apotheosis of Stirling’s mature manner,notable for its audacious combination of ‘pop’ constructivist episodes,clad in patent glazing and painted British racing green,with unabashedly neo-classical tropes ranging from the top-lit symmetrical enfilade of the galleries themselves to the Asplundian stone finish applied to the central cylindrical courtyard.

The completion of the Staatsgalerie inaugurated a new phase of Stirling’s architecture,in which it became increasingly postmodern and historicist. The phase began with his 1981 designs for the Clore Gallery extension to the Tate Gallery in London and went on to include his Sackler Gallery at Harvard University of 1985. A final transformation occurred in the second half of the 1980s with the Braun pharmaceutical equipment plant in Melsungen,Germany (under development from 1986 to 1991),designed in association with Walter Nageli in Berlin. These projects returned Stirling to the vernacular mode with which his career had begun,only now the reference was more agrarian in tone and derived from German,rather than British models. Built in rolling agricultural land,Melsungen would not only prove to be the most heroic and topographically inflected work of his career,but also the last major undertaking before his untimely death in 1992. The diminutive postscript to Melsungen was the Electa Bookshop realised for the 1991 Venice Biennale. Seemingly conceived as a typological combination of a beached barge and a greenhouse,this single-storey,pitched-roof building,covered with copper sheet,was something of a return to the diagrammatic but dynamic manner of his early brutalist period. There were significant differences however,most notably the long plate-glass window running around the building and the off-white stucco rendering of the walls,which,together with the verdigris roof,gave the building a Mediterranean air quite removed from the dour brick traditions of northern Europe. Melsungen and Electa jointly suggest a fresh beginning for Stirling at the very moment when his career came to a premature end.

Kenneth Frampton

He passed away on June 25,1992,London

Chronology

-

Leicester University Engineering Building

-

Stuttgart State Gallery and Chamber Theatre

-

Clore Gallery

-

At his office